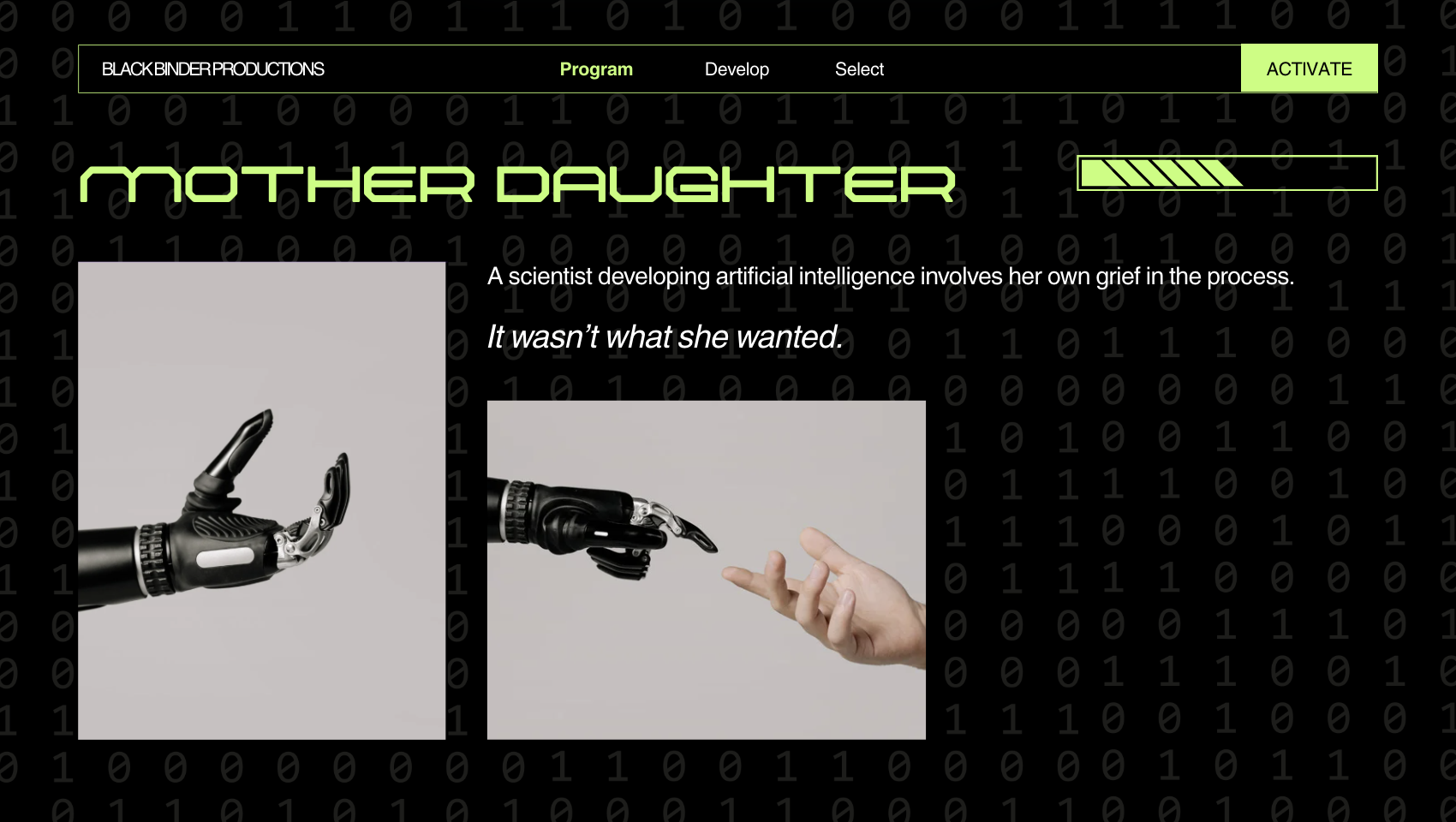

Mother Daughter

A scientist developing artificial intelligence involves her own grief in the process.

Mother Daughter was originally written for a class assignment interpreting a “creator meets creation” scene a la Frankenstein. I find the idea of motherhood and pregnancy to be ripe for horror because devoid of association, the idea of creating life from scratch and having it invade your body for a period of time is incredibly horrifying. However, the relationship between a mother and a child which was more of an idea than a person — a child before birth, or a child who died early — I felt was interesting in this context, and especially relevant to the discussion of “creator and created,” as the “creation” has less agency than a fully-grown child might. The piece has been edited and slightly expanded from what was produced for class.

Read Mother Daughter here:

It wasn’t what she wanted. That was the first thing she thought, when she saw it.

It sat lifeless on the lab table, synthetic limbs in stasis, hanging limply from a mechanical corpse yet to be covered with clothes. A triple-wound hardwired cord ran from the port on the side of its neck into the desktop computer, ancient and overused, which took up most of the space on the adjacent desk.

Hello, the prompt on the screen read. A green cursor blinked menacingly. What is my name?

She wasn’t going to answer the question, not until she figured out what to do with it, lying supine with no electrical power, as of yet, to animate itself. The programming dictated that the child would first establish its name and basic parameters. It was a failsafe, worked into the system a long time ago, before things like going to market had become forgotten in the haze of little imperfections and sudden anxieties. She held the keyboard in her lap and watched the cursor blink, and blink, and blink.

The child wanted a name.

In order to terminate the program, she would have to get past this screen. There was no way around it. She thought of a worn-out book of baby names on her nightstand, of a birth certificate filed at the county courthouse. Anne.

“My name is Anne,” the computer read aloud in a choppy, staticky voice. She turned the volume off; the words switched back to text on the screen. Please tell me who I am.

She looked to the thing on the table. She swore she saw one of its pointer fingers twitch, as if reaching out for something close enough to poke. She swore the steel eyelids were fluttering, and the chest was rising and falling with artificial breath. How long had it been since she had left the lab? Six days? Seven?

The cursor blinked and blinked. Please tell me who I am.

You are my child, she wrote, shoulders tensing. It was not true. It was not, she reminded herself, what she wanted.

Type Y to initiate program.

She put the keyboard down beside the computer and rolled her stool closer to the head, as yet unfinished. She could not bring herself to finish it. Each of the faces she had made had not been right – the eyes were just the wrong shade, the nose a tad too small, the teeth not quite crooked enough. In retaliation to her own deficiencies, she had left it a quivering, exposed mechanical brain, twisted wires and blinking lights. When she moved near it, she could have sworn it twitched.

She reached back and softly tapped the Y button. A loud whirring overtook the lab. On the table, the construction began to shudder, and then it opened its eyes.

“Hello,” it said finally, in a soft, high voice. The stock voice of a child, purchased from an audio library with a prototype license that had expired six years earlier. “My name is Anne.”

“No, it isn’t,” she said, but was hardly aware of herself saying it. What she had made blinked at her, faceless, unreal. It reached out its hand.

“I am your child,” it said.

“No, you aren’t,” she said simply. “My child is dead.”

It did not respond. It did not know how to process those words. She had not told it how to feel grief, for itself or for others. She had thought to save it from that emotion, back when she thought it was something that one could be saved from, rather than all-encompassing, swallowing mass.

“I am your child,” it repeated, trying to force order into a disordered universe. Once upon a time, she had fallen in love with computers for this very reason. She did not believe, after losing sleep for countless years – first in hospital waiting rooms, then in this very lab – that she was in love with anything anymore. “What would you like me to do?” the child asked, because it did not know that there was turmoil in her brain, that she was in need of someone to tell her what to do. “You created me. What would you like me to do?”

No child of hers would ever be so pliant, so accommodating, she had long ago decided.

There was a flaw in the code.

The child blinked at her in coded two-second intervals. She removed her eyes from its form and turned back to her keyboard. She did not look at the screen as she input the shutdown code, so familiar to her fingers that she was typing it against her sheets in the dark of the night when she couldn’t sleep.

As the shutdown process initiated, the thing on the table that was meant to replace her daughter jerked and shuddered and did not break eye contact with her. Its eyes, the only fully articulated parts of its body, filled with sadness. She did not know why. She had not programmed that.

When the code had been wiped from the central hard drive and the remote power systems had been shut down, she removed the cord from the port on the side of its neck and wrapped it around the desktop computer until it would need to be used again. She carried the body – deceptively light, so fragile – to the shelf against the opposite wall. It would sit in a neat line of bodies just like it, small and delicate, empty of life. The early iterations had detailed faces and wore pretty dresses with a child’s name stitched into the tag. Their hair was fine and combed. The later ones had patches of skin missing, revealing hard metal joints. No clothes. This latest one looked barely human – and, she reminded herself, it was not.

She shut down the desktop computer and hung her lab coat on the hook by the door. Tomorrow, a new shipment of materials would arrive. Tomorrow, she would try again.